The Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope

The Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope is an ongoing, ever growing, creative collaboration in honor of the North American freshwater mussel species Epioblasma torulosa torulosa or tubercled-blossom pearly mussel. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service declared these beautiful golden mollusks extinct on 16 November 2023, striking the species from the Endangered Species List.

To classify a species as Endangered is to acknowledge that its existence is important. Endangered species receive, as a matter of urgency, the public consideration and official protection that they should’ve had all along. To classify a species as Extinct is to simply give up on the possibility of its continuing presence in the world; declarations of extinction are ultimately based on no more than a lack of evidence to the contrary. Tubercled-blossom pearly mussels have not been seen alive by qualifying humans since 1969. It is a fact that anthropogenic activities have made the mussels’ riverine homes almost unlivable, but it is also a fact that these small, quiet animals are uncommonly good at hiding. Preserving what remains of their aquatic habitat would require overturning North Americans’ anthropocentric conceptions of freshwater resources, overhauling land-use policies, and altogether ceasing industrial and agricultural waste-dumping.

It’s far easier to declare, in a deliberate forgetting, that tubercled-blossom pearly mussels no longer share this world with us than it is to hope that they still do.

And so we artists set out on a journey of collaboration: creative cooperation with one another and with tubercled-blossom pearly mussels. Whatever co-creation might consist of in this context, it cannot possibly entail writing tubercled-blossom pearly mussels out of existence. Instead of clearing our consciences of them, wiping them out of our hearts and minds, we are living with them in the creative work that is the vital substance of our everyday lives. The labors of love that make us who we are, that give energy and meaning to our existences and compel us to go on—in every moment of this work, tubercled-blossom pearly mussels are with us, inspiring dedicated, fresh endeavors, permeating and mutating our thinking in ways that wouldn’t have occurred to us without these exquisite shellfishes’ intimate influences.

Under mussels’ strange and patient guidance, we are making works of literary art, photography, video, drawing, scrapbooking, sculpture, and sound. We are conversing, corresponding, and cultivating indissoluble friendships within a mesh of creative energy and hopeful dedication that stretches across oceans and continents.

The Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope was born of an invitation to create work for Delisted 2023 (of which more below). The mussels are so vivacious and beautiful that the Library has fabulously exceeded all expectations as the mussels inspire more and more creative energy, devotion, and hope in their artists. Tubercled-blossom pearly mussels have quietly drawn our attention not only to problems pertaining to extinction but also to other questions about creatively living together—and to other bivalve species. Our works must be consequently scattered among various venues (more of which we’re always seeking), just as each mussel species must disperse itself in different waters to survive. The Library is a safe space where our shellfishy works can be together and be gently held, regardless of where else they end up.

On this website, unless otherwise indicated, texts are by Mandy-Suzanne Wong and images by Lee Deigaard: portraits of a certain creek in which tubercled-blossom pearly mussels may have lived and may yet live. Special thanks to Heather Kettenis for assistance with the website. Curated by Mandy-Suzanne Wong.

Jennifer Calkins

The Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope began with Jen’s invitation to participate in Delisted 2023; an open space for attentiveness and creativity in hope and in mourning for the beings who were excised from the Endangered Species List.

Jen points out that most of the Delisted species are aquatic. Most are invertebrates. As terrestrial animals, we humans must go out of our way to meet them. Our imaginations must sally forth beyond our comfort zones.

Here, in places not our own, we tarry. Here the living yet exist with others bygone and possible. In careful proximity, here we hold these others still. We dream and work in their company. We invite them to recreate us from within. In Delisted 2023, Jen envisions:

. . . an emergent container to hold the space we need to mourn [the Delisted species’] precarity and to come within reach of their liminality . . . moments of quiet and ways to be with the more than human beings that were once, may still be, are, or are no longer with us now, in this moment in time.

Jen is holding space online for the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope and seeking opportunities to share it alongside other Delisted projects. She will contribute poetry and interactive creative exercises to the Library if she has time. She is arguing in court for the preservation of forests and other vital habitats.

By Jennifer Calkins:

“The Freshwater Mussels: A Tiny Introduction…”

Creative Comment to USFWS on the proposed delisting of two more freshwater mussel species, the Chipola Slabshell and Fat Threeridge

Homepage: Jennifer Calkins

Gretchen Primack

Gretchen composed the poem “Tubercled Blossom” especially for these mussels’ Memorial Library of Hope. The poem debuted aloud at Graveside Variety in Woodstock, New York and featured in the 2023 Compassion Arts Festival.

Graveside Variety is named for a burial ground exclusive to human artists. Such is infinitely preferable to memorializing murderers. But how much land and water the human dead require! We’ve little room to spare for other-than-human living, almost no room at all for shellfishes as living neighbors, not even on our lists of who counts as precariously living. The less that other beings resemble ourselves, the more forgettable they tend to seem to humans.

Between Homo sapiens and tubercled-blossom pearly mussels, Gretchen’s poem listens for kinship. Finds its ancient, quiet forms. Feels kinship keenly. A marvelous side-effect of creative collaboration with mussels: we’ve begun to see them everywhere. Or their traces. Or their shadows. We’ve begun to see our forms in their light, our words and images through their siphons through the careful opening between their shells. Only after completing the poem “Tubercled Blossom” did Gretchen see how bivalvular is the thing that she had made. The poem emerged in two parts: two valves, as a mussel has. Each stanza, likewise, is a pair of utterances. In the poem’s very shape and body, its subject and inspiration find itself. The tubercled-blossom pearly mussel finds itself in a new form. Like a powerful medium, Gretchen summons this mussel from the unbridgeable distance of their aquatic otherworld into a perceptible, handmade form: a poem that with sure aim and true speaks to what we are.

Considering that millions of pearly mussels perished in order for their shells to become ornamental buttons, Gretchen’s poem “What Not Ours” makes an apt companion to “Tubercled Blossom.” They appeared in About Place in 2023 and are reproduced below by kind permission from Gretchen.

By Gretchen Primack:

“Tubercled Blossom” and “What Not Ours,” About Place Journal

Homepage: Gretchen Primack

Two poems by Gretchen Primack

Tubercled Blossom

Firmly muscled and lightly mussed

in their pearl, a must

for millennia, a tired number of millennia,

a tired number of mussels, as glad

as we are

to be in the world.

And the patience! Kissing halves

calcified tough in calcium and slick,

native in a way I am not,

endangered in a way

I am not, class bivalvia

unlike me, phylum Mollusca

unlike me, kingdom Animalia

like you.

Highly impearled, highly imperiled,

muscled hearts keening my heart,

stone blossoms hinged and mantled

and finely fibered—

suddenly unhoused,

ungilled,

unplanktoned,

suddenly silted out of the world.

May I, the unendangered—

may my mighty species, weak

hair, grey teeth, cut skin—

may I

elegy?

What Not Ours

When I asked my grandmother how her day was, she’d say,

“I had to kill them little chickens. I had to kill them little chickens.”

—Kiese Laymon

—and if we threw the lever, stilled

the line, righted their clasped flapping

selves, cooled the scalding tanks,

buried the knives, held each body

to a damp ground, to seeds

and roosts, Fall in her damp

brown dress calling for roosts and seeds,

feathers as protection, gloss, vanes contoured

and valued on her neck, wings stretched and loved

at her sides, wings splendid and muscled

for the stretch, her breast’s red heart snug

in its beat, her cells knit into the fibers of her

for her life’s work,

that not ours—

Joanna Lilley

All the literary artworks in the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope were conceived and composed independently of one another. Hundreds of miles, in some cases thousands of miles, oceans, cities, rivers, forests, mountains, separate the artists from one another. Our one precious point of contact: the mussels themselves. Our hope and care for them, rather, the urge to work and the inspiration that are their unsuspecting gifts to us.

In Jo’s pair of poems for the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope, the mussels gently but undeniably exert themselves, their forms, their ways of life in riffling waters among fishes and other beings. Human relations with tubercled-blossom pearly mussels are less than committed, the poems imply: ours are incomplete, nonreciprocal relationships in which we look right past each other. Oftentimes our touch, each against the other, is oblique and unconscious—but not the less sharp and penetrating despite being unacknowledged.

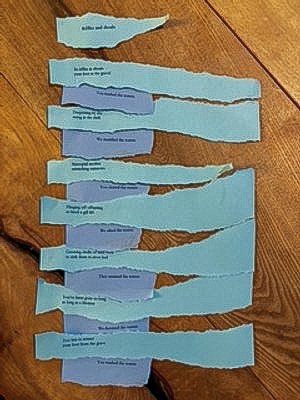

The poem “Riffles and Shoals” is suffused by bivalvular forms on which Jo’s rhythms riff. In a self-enclosed and rounded-off, shellfish-like form, the poem holds itself together with the foot of the mussel who, suspended between possibility and extinction, both exists “in the gravel” of its native riverbeds and calls out “from the grave” to which humans condemn it by damming and dirtying. In a sort of ghostly chorus of italics, mussels and humans call out to each other between the two-line stanzas in which the mussel goes about the business of living.

In riffles in shoals

your foot in the gravel

You washed the waters

Deepening by day

rising in the dark

We muddied the waters

—From “Riffles and Shoals”

In “Skinbearer” is a scientist who probably isn’t human, is possibly a dragonfly or some other soaring skimmer who brushes the river but lightly while “human offspring” unthinkingly disrupt it. Awash with ambiguities, this poem refuses to pin anything down; like mussels costuming themselves in mud and brown shell-tones, the scientist deliberately evades the curious human gaze.

She knows what needs

to be collected to expose

the deep blue seaprint

of an invisible universe

that she’ll float downriver

to the waterverse

each day until a species

salvages it.

—From “Skinbearer”

Reflecting on her work for the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope, Jo kept a journal and scrapbook. Below are her photographs of her creative process, thinking with fragments, gravel, and riverine stones.

By Joanna Lilley:

“Riffles and Shoals” and “Skinbearer” are seeking magazine publication

Homepage: Joanna Lilley

Mandy-Suzanne Wong

More than any convocation between the artists, it was the mussels who caused our texts to emerge in bivalvular forms. Their histories, their will to live, and at least some of their aspirations for themselves, all of which shellfishes archive and express in the forms and eccentricities of their shells, riffled our imaginations from across vast thresholds of time and space, forgetfulness and death. All unwittingly, invisibly, these quiet animals convene us, the cilia surrounding their little siphons tremble the water, and we resonate their vibrations—they move us to empathy. We primates of the thoughtless species that is their greatest enemy!

Empathy is my effort to feel as you feel but in my own way. As a practice and an experience, fiction can be intensely empathic: it is the art of feeling the emotions of a stranger in and through one’s own language.

“Notes From Underwater” is a two-faced story, a bivalvular work of hybrid prose at once fiction and “fan non-fiction.” We visit with a singular tubercled-blossom pearly mussel who refuses to be a mere multiplication operation of her species. Not everyone lives their world in the same way, even within a shared environment. Committed to a life of contemplation, our mussel survives the anthropogenic extermination of her community and the several hundred years to which freshwater mussels are entitled. She is an outcast from a species (shellfish) which, according to those who count (humans), itself doesn’t count for much. Consequently her ideas and experiences resonate across the centuries with Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky’s great novels, which were born of painful empathy with individuals who did not count, whose paradoxical personalities sidelined them from every position.

She’s after all a bivalve, two-faced to the world, a headless foot in a hinged two-sided shell. With two outsides she’s her own double (Epioblasma torulosa torulosa); cleaving to herself with her ligament, cloven from herself where her shells part from each other at her discretion. A flicker of the light can change her mind from “closed” to “open.” And nothing is simply this or that with her. Both sides of a matter may occur to her in the same instant; a morsel both vile and delicious, a notion both perceptive and stupid in a single moment. […] But perhaps you’re one of those humans who thinks only humans think. Therefore if I, your narrator, propose a shellfish who’s obsessed with lofty questions, you think I’m mistaking a shellfish for a human and even doing it on purpose. And if I, your narrator, happen to be just such an inquisitive shellfish, you’ll discount everything I’m saying, just because. One hopes you’re not a stick-in-the-mud when it comes to reckoning who counts.

—From “Notes From Underwater”

Love and hope for molluscan individuals are frequent catalysts of creative energy and new work for me. Curating the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope, and creating original prose with and for a very special musscular individual, I found myself rereading my previous molluscan writings in tubercled-blossom-pearly light. If the defining attribute of the extinct is the ability to pass unnoticed by qualifying humans for several decades, then as I wrote some years ago, the greater Bermuda land snail (Poecilozonites bermudensis) evaded anthropogenic extinction by appearing to be extinct. Tubercled-blossom pearly mussels could theoretically do the same. In a life-changing encounter with a milk snail whom I called Toru (Otala lactea), I discovered that caring relationships between molluscan and human individuals are not only possible but also powerful. And then the echo—Toru, torulosa—between the first snail I ever loved and the Delisted bivalves whom Jen Calkins consigned in absentia to my care: co-incidence as coexistence.

Co-occurrences of this nature give me hope for tubercled-blossom pearly mussels even in an anthropocentric world. Such coincidings, incidences of being together, affirm that of course shellfishes count, and even a human can experience their significance as acute emotion to the point of feeling moved to personally assist individual mollusks in distress. I offer links to these earlier writings below in hope that they may nourish the various energies of the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope.

By Mandy-Suzanne Wong:

“Notes From Underwater,” Cincinnati Review

“Introducing Kiskadee,” Manqué (rebranded as Talk Vomit)

“Singularity,” Litro

Heather Kettenis & Mandy-Suzanne Wong

This pair of lifelong friends is collaborating on a diary and scrapbook of our work and feelings with tubercled-blossom pearly mussels as the latter bedded down and burrowed deep into our sediments. Fragments from research materials, notes on our ways of thinking, poetic quotations on extinction and loss, pertinent scientific terms and diagrams, pauses for mussel-like contemplation and silence written in musical notation, attempts at drawings, handwritten stories of musscular melancholy, handwritten fears and hopes for mussels, handwritten celebrations of other artists’ contributions to the Memorial Library of Hope . . .

In scrapbooking we have a bivalvular relationship: one of us takes in and filters the materials, the other puts them together. One siphons, one holds. Holding the two-volume scrapbook is a pair of journals handmade by humans from corpses of nonhuman animals and plants. The books were given to us by our beloved siblings (who are also artists) to foster and encourage our creative work. Death and life, despair and hope, love and dreaming run through the very bodies of our scrapbooks like memories of rivers. Fragments of our work and others’, fragments of silence, beginnings and failings: in such “scraps” as these, tubercled-blossom pearly mussels manifest their presence, nonpresence, and potential.

Scrapbook photos by Heather Kettenis coming soon.

Lee Deigaard

Lee is a lifelong neighbor to tubercled-blossom pearly mussels, who inhabit fresh flowing waters of the southern United States, including the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Ohio rivers and the streams and creeks of Georgia and Louisiana. The waters ought to run through lush variegated forests. Some of them still do. Owls, deer, hawks, coyotes, squirrels, bobcats, land snails, butterflies, snakes, and many vivacious others share the forests with the waters. Beavers, fishes, turtles, aquatic snails, dragonflies, cormorants, alligators, and a bevy of beautiful others share the waters with the mussels. Trees such as red maple, chestnut oak, sycamore, tulip poplar, and huckleberry share the banks with bushes, grasses, wildflowers, butterflies, and other pollinators.

Lee knows where reservoirs ought to be rivers, where water that lies flat and tame ought to be wild, undammed. Day after day, Lee witnesses the destruction of the homes of plethoric beings by their human neighbors. She has seen non-molluscans throwing garbage from car windows into creeks beside which, to the waters’ great misfortune, interstate highways rush and roar. She has seen fuel tankers overturn on the highways and vomit their toxic cargo into the waters. She has seen, on the riverbanks, thrown-away things of every size and synthetic composition. She has seen agricultural sewage flowing into streams. She has witnessed beloved waters wither away almost to nothing in droughts made endless by climate collapse.

Of interrelationships between those who share her habitats, Lee is a devoted observer. Snail on stone in water. Beavers’ bite marks on boles they’ve made to lie across the water. Cow fallen in the water teaching herself how to live human-free. Lee doesn’t hunt for mussels. She does not disturb the waters. She sometimes finds the dead of various mussel species on the banks: empty shells which could cradle baby fishes. In photography, writing, drawing, and other forms, Lee bears witness to loud and lasting, quiet and fleeting interactions between the individuals who make and live their ecosystems—which, with hope, tubercled-blossom pearly mussels may yet share. Her writings celebrate ways in which, wherever they are, mussels and their nonhuman neighbors are shaping her ideas of how to be a better Earthling.

In her prose improvisation, “The Library of Love,” living energies suffuse one other with magic, disparate beings cleave to one another through breath and filtration, metaphor and touch.

Lichens and fungi grow upon the biggest oldest books of Love. Also mussels on the parts of spines submerged. In the Library of Love no one ever opens a book until that book has released its clench (what is the muscle which mussels use to keep their shells closed? That one.) The books In the Library of Love open readily, but readers must not grow impatient. […] The Library of Love is writing itself as it lives and breathes. It has an exoskeleton. It is an exoskeleton which is to say it is all windows and free passage and alveoli. Coral reefs and beds of mussels—their memories are what make the exoskeleton. A book aspires to be a bivalve. A bivalve holds within, takes from without, releases and filters. The bivalve and the book are witnesses and records of their own singularity. On particularly ardor-ful days, the exoskeleton appears to open all over, a complex surface of little stoma embedded within, a chorus of pores opening and lightly closing. […] The Library of Love is a rigorous place. Upon entering, one is on one’s toes, not least because the tidal flow affects us all differently according to height and whether we have gills or feathers. Fur or, what is most pitied by its denizens, naked skin.

—From “The Library of Love”

Lee is also drawing portraits of tubercled-blossom pearly mussels and making photographic portraits of a certain creek which might have been and may yet be these mussels’ home. Her photographs tremble with the vivacity of water: the creek is a living Earthling with personalities, gestures, moods, and colors all its own. Her drawings take the mussels’ ghostly images, memories of their empty vessels, into her hands, into her life; even as the shells’ scattered arrangement on her page—sometimes as if systematic, as in a specimen drawer, sometimes scattered across untextured space—evokes the distance, perhaps unbridgeable and absolute, which today marks the relationship between tubercled blossoms and human viewers.

By Lee Deigaard:

All photos and drawings on this site unless otherwise indicated

“Tubercled blossom pearly mussels,” drawing (upper right)

“Tartan for the Lost Clan,” photographic drawing (lower right)

“Here you were, the light within,” photograph (below)

“The Library of Love,” essay

Homepage: Lee Deigaard

Janell O’Rourke & Vincent Evans

In Woodstock, a town perfused by brooks and creeks, when Janell heard Gretchen read her poem, “Tubercled Blossom,” and discuss the mussels with me in the context of Delisted 2023—inspiration struck. Janell felt drawn, intrigued by these small animals who exist out of sight in hush. She was moved to make a film in their honor.

An ode is a lyric of praise. “Ode to Tubercled Blossom Pearly Mussels” celebrates with quiet wonderment: mussels alive! The film imagines precisely this, tubercled blossom pearly mussels safely nestled in their riverbed, doing what mussels do: opening their shells and closing them, reaching out with their siphons, filtering the water and enjoying its nutrients, relieving it of detritus. Janell’s stop-motion animation has a handmade feel to it. A loving, care-full feel. It is almost if Janell’s film is holding the mussels in her hands. Or rather: the mussels are safe at home underwater, held there carefully by Janell’s homemaking filmmaking.

Vincent Evans’ soundtrack, created from found sounds, includes recordings of the family cat, Malcky, drinking water—cool, clean water which, like most of North America’s freshwater resources, could have come from a river (or a reservoir that is the ruin of a river) which ought to have been a home for mussels. Malcky’s innocent lapping softly sounds out the intimacy between humans’ homes and mussels’, between humans’ and mussels’ basic needs for water and shelter. In Janell’s film, tubercled-blossom pearly mussels are as much part of her family as Malcky is.

The film is bivalvular: it is in two parts. Both parts call attention to mussels’ agency: their ability to accomplish things, affect their world, give shape to their own lives. The first part lingers with the mussels eating and breathing, cleaning the water as they do so. The second part invokes the collective voice of shellfishes, who describe the work of shell building as artistic, architectural, unsung homemaking.

we are sculptors really—we build our own homes. our skills take into account practicality durability and of course aesthetics. our exteriors tend to be subtle—we don’t need to call attention to ourselves. while our interiors are jewels of pearlescence.

—From “Ode to Tubercled Blossom Pearly Mussels”

Below, in Janell’s drawing collage entitled art is not human, the depicted mussels are either inhaling or exhaling particles, either gathering fresh materials for auto-sculpture or painting the water’s taste and fragrance. How their creativity functions is ambiguous. Likewise are the mussels’ shadows and the pervasiveness of darkness.

Millions of North American freshwater mussels were murdered for their inner glow. In one form or another, humans sought to ornament our exteriors with mussels’ private nacre. Unable to cultivate their beauty within ourselves, we stole it. But in vain. Ripping mussels out of their self-sculpted bodies for the sake of pearly buttons, freshwater pearls, or marine pearls cultured from mussel-nacre nuclei only made us uglier.

By Janell O’Rourke and Vincent Evans:

art is not human (below)

Homepage: Janell O’Rourke

Below: “Ode to Tubercled Blossom Pearly Mussels” (film stills) and art is not human (drawing collage) by Janell O’Rourke

Stephanie Niu

In the Library’s bivalvular spirit, Stephanie composed a pair of poems that face each other. They reflect each other not as in the closed circle of mirror reflections but as in the rippling of images in water, the movement of which suggests new forms.

The prose poem “Buttoning in Muscatine” describes the death and effacement of pearly mussels in early twentieth-century button manufacture, from the moment of the mussels’ capture to that of the satisfied customer donning a garment with luxurious mussel-shell buttons.

Workers soak the new shells soft, cut out round blanks with saws. A lathe applied to a new button’s face creates a fashionable design. As does a nice shade of coal tar aniline dye. Workers drill holes in the cut blanks and polish them with muriatic acid, tumbled pumice. The shell fragment is ready to fasten garments.

—From “Buttoning in Muscatine”

Contrastingly, in “Mussel Reproduction,” mussels “wanted more life and got it.” The poem describes the cunning of certain freshwater mussels including tubercled blossoms, who, with the magic of shape-shifters, attract fishes with deceptive lures in order to implant their larvae in the fishes’ gills.

Mussels grow fins and tails,

hint of a gill, to imitate

their origins in pulsing lures.

Finned and shelled, free

and sessile– while we

need to be owners, only

beings making repeatedly

ourselves– river beings live

by different rules, permit

their mirrors everywhere.

—From “Mussel Reproduction”

By Stephanie Niu:

“Buttoning in Muscatine” and “Mussel Reproduction” are seeking magazine publication.

Homepage: Stephanie Niu

William Woolfitt

William Woolfitt has been thinking and creating in collaboration with quiet places and small nonhumans for several years—including tubercled-blossom pearly mussels. “After the Button Factory” first appeared in his collection, The Night the Rain Had Nowhere to Go. It’s the Library’s privilege to reproduce the poem in full, with Will’s generous permission.

The button factory dies because the mussels and the river died or sickened to keep the factory alive. In Will’s poem, we see humans, mussels, and river all entangled in the consequences. As “too much button polish sours / the river,” the humans look and long for “dreams of pearly mussels.” But it seems that even dreams elude the defunct factory’s workers who, unemployed and in despair, burrow mussel-like into their beds.

After the Button Factory

by William Woolfitt

The sun clambers over the husk

of the dead button factory, brushes

the tarp-roof of our fishing shack.

We burrow under pillows, could be

tubercled blossoms who take it slow,

mimic stones, sink from light

with dreams uncountable, old

as rivers—who bed in cobble

when braillers fork them up, cut

their shells for round button-blanks—

who by becoming scarce outlive

the factory that belly-ups after

too much button polish sours

the river, softens too many tubercled

blossom pearly mussel shells

to puce jelly. Spilling into our shack,

the sun dampens hair, poultices our

skin with sticky heat as we pull on

dungarees, slip outside, put our

dream-heads in blue Lowe’s buckets

with plexiglass bottoms, try to see

dreams of pearly mussels in green-

rayed golden shells tubercling

the muddy bottom, rose nacres lining

their blossoms—try to net spooneys,

flatheads, relic-fish with no bones,

no teeth. Mile-a-minute vines

swallow the rusty factory

while its afterimage

and mussel dreams linger,

sieve and sheen the water.

By William Woolfitt:

Kathryn Eddy

The shell of a tubercled-blossom pearly mussel is an expression of her innermost. From her soft little body oozes the ooze that hardens into her aragonite exoskeleton, sunshine yellow and mud brown. Each year, like the boles of the trees that are her neighbors, her shell grows one more ring. The chemical qualities of the water in which she lives, the depth of the water, and how it flows determine the size and thickness of her shell: we might say she lives the water, the water which she lives as. The size and strength of her water decide her shape, whether she is soft and elliptical or angular and almost pyramidal. Her shell is her self-formed two-sided shield, the mask that’s her true two-faced face; the two sides of her shell, its dual valves, are her covers and the pages on which she inscribes her life story. Food shortages, acid in the water, violent encounters with hands or stones: she will document them all, a living archive. Her shell’s inner side, her nacre or mother-of-pearl, is absolutely private, exclusively her own. And she defends it with her life, with the two golden shields which are the only chronicle of her existence. What became base material for mass-produced buttons and cultured pearls thus includes her species’ history. For the erasure of an entire bivalvular people’s past, presence, and future, humans are responsible.

I am envisioning the creek beds down South where I grew up. My brother and I spent as much time as possible following the path and playing in the creek near our home. I like to think that the [mussels] were abundant in the water as we passed by. We felt such a sense of love and care for that little stretch of creek and such disdain for the encroaching development taking place around it.

—Kathryn Eddy in conversation

A favorite technique among humans for commemorating accomplished or ideologically significant persons is the memorial sculpture. When Kathryn Eddy places her life-size sculptures of tubercled blossom pearly mussels in the creek behind her home, it will be the water that has the chance to honor them. For human audiences, Kathryn will film the sculptures in the creek amidst the water’s caresses and voices. Humans and mussels will be present to each other obliquely, their differences celebrated in all their irreducibility.

In the very act of sculpting, the two life forms’ perfect otherness relative to each other manifest as felt experience—Epioblasma torulosa torulosa versus Homo sapiens sapiens. Sculpture is all the more challenging in the absence of the living subject, Kathryn says, for she conceives this work as very much a collaboration; the sculptures are expressions of the mussels’ working on Kathryn’s imagination. But because simian hands are so different from molluscan mantles; where the mussel would exude from within both her material and its form, Kathryn must make her shells by molding preformed material from without. Her use of polymer clay bears witness to the pervasiveness of plastic pollutants in mussels’ lives. In the wistful spirit of the Memorial Library of Hope, Kathryn imagines: if only the mussels could digest the ubiquitous microplastics and render their own shells as indissoluble and immortal.

In a bittersweet mode of speculative listening, Kathryn spent months imagining what plastivorous mussels of the future might like to say to humans. Though they be handmade and not secreted, her speculative mussels’ words are so blatantly anti-anthropocentric that Kathryn’s project cannot be mistaken for anthropomorphic. Instead of “giving voice” to the mussels—as though the mussels hadn’t voices of their own already—Kathryn’s goal is to hold open a carefully empathetic space wherein mussels’ aragonite voices may make themselves imaginatively heard. Rather than etching words into the clay, Kathryn playfully functions as a sort of medium through which the mussels’ sentiments emerge from the clay with and as their storymaking shells.

By Kathryn Eddy:

Photos, video, and sound recording coming soon

Homepage: Kathryn Eddy

Below: The Angry Mussels by Kathryn Eddy

DULSE

The Duo Undertaking Listening to Shelled Earthlings is two-sided, of course. We are metaphlorists and bivalvular irritators on behalf of the nacreous.

One of us has never seen freshwater mollusks, hadn’t imagined them or even suspected their existence before the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope came into being—for that one’s habitat has no rivers, no creeks, nor even saltless ponds. The other may well share habitats with tubercled blossom pearly mussels.

We think and dream together in interstices of algorithms and airwaves, co-creating careful forms and practices of being. We play our computer keyboards in simultaneous, real-time writing improvisations: our Duets of discovery are wanderings in words and rhythms, wondering at startling convergences, thought-twinnings, timbral doublings occurring spontaneously between us and within our shared language. With tandem siphons we sift our prose wanderings and others’, we filter the fragments as with sensitive gills, and digest them into centones or collage-poems.

Thanks in part to tubercled-blossom pearly mussels, we have come to love all mussels. We love thinking with them and feeling ourselves and our worlds becoming porous with seeping colors and sparkles under their quiet influence. At our request, Jen Calkins recently consigned all Delisted shellfish species to our creative care.

In the Mussels’ Memorial Library of Hope is hope that dares to be without asphyxiation. Its books are bellows. To read is to respire. Against almost certain expiration. Every inhalation is an act of hope because it is porosity. Because it is necessary. Every exhale an act of peace. If it is not shouting. Closing her valves, shell to shell cleaving uncloven, she gives her peace to the creek. And the creek carries it. The creek in peace flows through. The creek is a herald and its broadcast the exhalations of mussels. (No, its medium. Its own breath). The creek breathes for itself. And fishes dragonflies and freshwater crabs and the hope of humans hoping to live another day and birds and those who inspire through their roots like mangroves. The heron’s legs, the tree roots, they hold and mark. How the creek wanders. How it surges and floods, idles and eddies. The water column is a recumbence. Odalisque, indolent and urgent both. The creek is the column but also its margins or membranes of mud and bank, leaf and rock. It reflects the sky, the creek paints and breathes… Because of the creek, how the creek goes and flows, mussels who are its capillaries know there is an afterlife. For this creek, which once was sky then cloud then droplet, will be ocean one day. It begins in the waters of the head, the headwaters and flows to the toes. Insofar as new water runs in the creek’s bed, the creek remains itself – which is to say it passes to remain itself. Where is the mussel who dreamed her double in the ocean? Calling out and being heard? Its measure is breath, its currency of exchange and transmission. Shells golden in the creek, shells blue-black in the salt and on the pilings. The afterlife is blue. There is no other color empyrean and oceanic. Deep and stratospheric. It is a mystery the necessity of which is also mysterious. Violet, blue, and green enter the euphotic zone. But blue travels deepest and clearest. Some primate species believe there is almost no blue in “nature.” Tell a blue mussel that she does not exist.

—From an untitled Duet (12 June 2023), improvised and unedited

By DULSE:

“filter-feeding poems for filter feeders”

“Dynamic Hierarchy (Sampson’s Naiad)”

“MUSSELMANIA!”

L.A. Watson

Living in the US south, on gorgeous land with a living creek which has been in her family for generations, L.A. Watson describes her home and her entire life as “cocooned by mussels.” The land itself, the property on which she lives, has the shape of a bivalve. Her hoary house, built in the eighteenth century, was constructed of limestone and mortar concocted from the remains of deceased shellfishes. For the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope, L.A. took compost, soil, and clay from her creekside home and with her hands shaped them into mussel-cular forms.

Originally her plan was—just as living mussels release their gametes into the water (or, in the case of tubercled-blossoms, loose their larvae upon the gills of unsuspecting fishes) to be swept up into the life of the Elkhorn creek—for her mussel sculptures to release seeds into the air, the seeds of water willows which would contribute to a healthier habitat for other mussel species.

However, L.A. says: “after doing more research I realized the American water willow plant would fare better as a rooted propagated plant rather than being dispersed as seeds. We have had a slew of severe weather in Kentucky this year [due to climate change], with flooding, severe storms and what seems like nonstop rain! All of that delayed my ability to reach the water willow at the creek, but I was finally able to set out a first batch of mussel seed bombs, which I'm now calling growth vessels. I chose an area of the creek where water willow was not currently growing in hopes of creating a new stand of it. Now that I have plants, I can continue to make new batches of growth vessels and continue propagating the water willow into new areas of the Elkhorn creek.”

Are not these sculptures living beings? Their bodies are organic, made literally of the land; they receive their shellfish forms directly from L.A. Watson’s human-animal hands. The sculptures are mortal; they will slowly crumble back into the land. But before then they will disseminate their descendants: the plants which themselves will live and give life to the land, their roots communing through groundwater with the creek. Remarkable multispecies beings these sculptures are: hybrids of terrestrial, aquatic, and vegetal life—and of human artistic creativity, the products of which it may not be entirely fair to call inanimate.

L.A.’s growth vessels straddle the thresholds between extinction, erasure, and death—and restoration, history, and life. How wonderful that, for the artist, they are but beginnings of work that she hopes will be lifelong.

In 2025, Jennifer Calkins led all Delisted 2023 participants in creative commenting at the US Fish and Wildlife Service in protest of their proposed removal of two more freshwater mussels from the Endangered Species List: the Chipola Slabshell and the Fat Threeridge. Our comments were artworks, many of them selected from the Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope. By law, the USFWS had to review all submitted comments, whatever form they took, before moving ahead with their decision. The full complement of Delisted 2023 comments is available here.

LA Watson created a photographic outcry on behalf of the Chipola Slabshell and Fat Threeridge: that they not be given up for dead, consigned to the oblivion of the forever forgotten.

The titles of LA’s images serendipitously form a poem.

I reside outside of prescriptive frames

and can be quite elusive

holding space between

in the shadows

we will always live here

we will always live here became the seed of a new project, which continues to grow. The land surrounding the Elkhorn creek, L.A. says, “was underwater once and ultimately may be again. In the midst of all the rain and storms we've been having due to climate change, I've used old photographs from the renovation of our old stone house that feature the tools of renovation scattered about the floors, which are now inhabited by mussels in a post-human world. They are now doing renovating of their own.”

By L.A. Watson:

Below: growth vessels, site-specific sculptures

Below: creative commenting for USFWS

Below: we will always live here

Homepage: L.A. Watson

I reside outside of prescriptive frames

holding space between

in the shadows

we will always live here

and can be quite elusive

More to come

The Tubercled-Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope remains under construction.